For the past two years we have been working hard to develop and improve our New Trust Update Archive Database to fully make use of the ever-accumulating data we hold on newly-created UK grant-makers. The database contains information on nearly 4,000 active trusts that have been featured in our monthly New Trust Update reports since 2005, the majority of which do not appear on any other leading directory.

What’s new and what’s improved

In March 2025 we launched the new and improved Archive Database, which is available to New Trust Update subscribers alongside the monthly reports on newly registered trusts. The main changes and improvements from the previous version of the online archive database are:

Accurate and up-to-date data

We have reviewed all the active trusts on the database and gathered accurate classification information on their areas of activity and geographic area of benefit, reflecting who, what and where tend to get the trusts’ support. This is based on their stated interests, activities, accounts, website and grant-making.

Detailed activities classification system

We have expanded the activities classification system from 11 categories to 28, allowing for far more targeted searches.

Granular geographic area of benefit system

The detailed geographic classification system, going down to the regional level in the UK and continental region level internationally, allows you to find funders for causes or projects in specific UK and international regions.

Regular updated data from the Charity Commission

Contact details, trustees and financial information for each trust are regularly updated from the Charity Commission.

Grant history

Where available, we have gathered details of the grants awarded by the trusts and foundations. As well as displaying these grants in the trust’s profile, we have used this information to allow searches on grant capacity as well as direct searches for competitor funders.

Additional flags and classifications

When reviewing each trust, we add flags to indicate whether a trust is a corporate foundation, if they explicitly do not accept unsolicited applications and whether they are a ‘Foundation of Wealth’ – established by a philanthropist whose wealth is estimated to be in excess of £10m.

Constant additions and maintenance

Newly registered trusts are reviewed after three years, with their Activity and Geography classifications updated. New grant data is constantly added, helping to build up a picture of the trusts’ interests and activities over time.

What’s in the database?

As of March 2025, there are 3,498 trusts and foundations on the database. We have analysed the data to gain an insight into noticeable trends or interesting statistics regarding the UK grant-maker landscape.

A full overview is available below, but the key highlights are:

Activity type

We have expanded the range of activity type categories from 11 to 28.

In some cases we have split out existing categories such as Arts, Culture, Sport & Recreation becoming Arts & Culture and Sports & Recreation or Religious Activities becoming Christianity, Judaism, Islam and Other Religions.

We have also created new categories such as Mental Health, Hospices, Higher Education, Research and Armed Forces to reflect the funding priorities of our subscribers.

This gives users the ability to be far more targeted in their searches, and fewer irrelevant trusts being returned.

As we have seen when we have analysed the database before, the most common activity type is General Charitable Purposes.

Many trusts are registered with General Charitable Purposes when they are first established meaning, in theory, they are willing to consider any type of charitable activity. However, as part of our review process we look at the grant-makers’ actual activities and interests, including their grant-making patterns, so over time we are able to classify these trusts more accurately.

After General Charitable Purposes, the best supported areas of philanthropic activity based on the number of grant-makers are Welfare (broadly helping those who are disadvantaged), Education & Training and Health.

Geography

Overall, there are 2,941 trusts that state they will support organisations and causes across the UK, and 2,101 that will support work overseas. 769 trusts report or show a regional preference within the UK. Our granular geographic area of benefit classification system allows users to find local funders for their projects across the UK or in specific regions around the world.

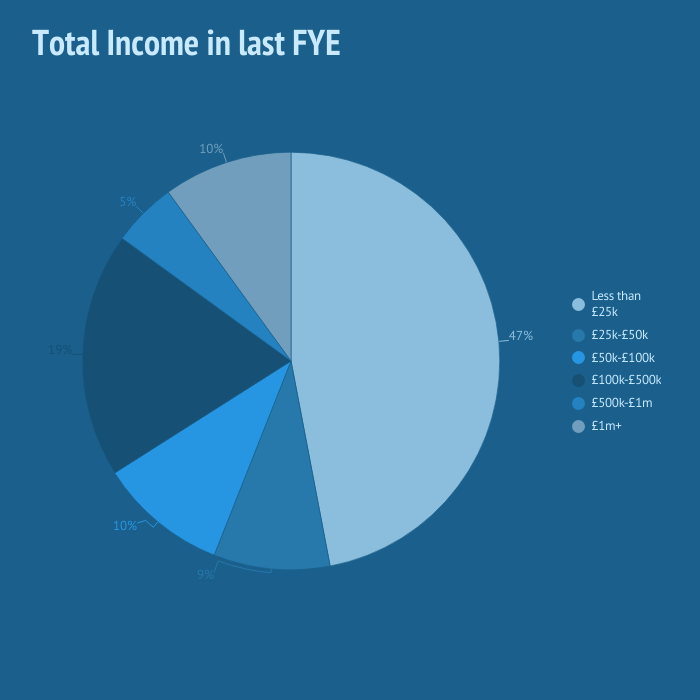

Income

The largest proportion of grant-makers in the UK remain small, with an income of under £25,000. However, over one in three of the grant-makers registered in England and Wales, and featured in the New Trust Update archive database, end up having an income of over £100,000, and one in ten have an income of over £1m. Past research has shown that many of these reach this level of income and expenditure within the first few years of operation.

Grants

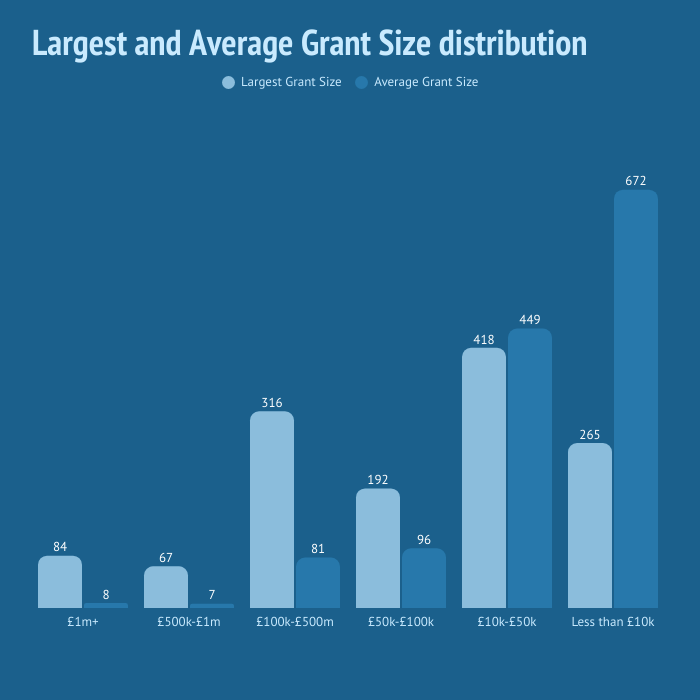

Where available, we have gathered recent grant-making histories for the funders in the Archive database. This allows us to see a funder’s grant capacity (largest grants awarded) as well as calculate an average grant amount.

This shows that overall 80 per cent (over 1,000) that report on grants have a demonstrated capacity to give grants of £10,000 or more and over a third have the capacity to make six-figure grants.

However, when we look at the average grant amount for each funder, we see that half of them are most likely to award small grants of under £10,000. This is in keeping with the total income figures above, and backing up the fact that the majority of grant-makers in the UK are small, with only a minority growing to be able to offer large grants.

We will be analysing the data contained in the Archive Database in more detail in the coming months and sharing further trends and insights from the UK grant-making sector.

If you would like to learn more about Factary’s New Trust Update service and get an online demonstration of our new and improved Archive Database please contact Will Whitefield at will@factary.com.