If you had any doubts about “major donor” fundraising – at Factary we use the term “strategic donor” – then today’s article by Martin Wolf should help dispel them (Wolf, M., 2016. The economic losers are in revolt against the elites. Financial Times).

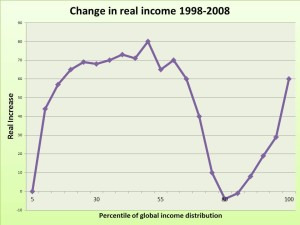

In the article, Wolf reviews the work of Branko Milanovic, previously Lead Economist at the World Bank’s research department, who showed in a 2013 paper (Milanovic, B., 2013. Global Income Inequality by the Numbers: In History and Now. An Overview. Global Policy (May 2013), pp.198–208.) how personal incomes for the majority of people in Europe and the US have stagnated whilst the incomes of the wealthiest 10% have grown. This we knew from other studies of the wealth gap. But what makes this chart so interesting is that there is another group of people whose incomes have stagnated – the poorest 10% globally.

Change in real income between 1988 and 2008 at various percentiles of global income distribution (calculated in 2005 international dollars)

Notes: This is global income, so the middle class in Europe is in the 70%-80% range. The vertical axis shows the percentage change in real income, measured in constant international dollars. The horizontal axis shows the percentile position in the global income distribution. The percentile positions run from 5 to 95, in increments of five, while the top 5% are divided into two groups: the top 1%, and those between 95th and 99th percentiles.

So here is a demand and a supply argument for strategic donor fundraising. On the demand side (of the non-profit world) the poorest of the poor are staying poor or getting poorer. Non-profits have more to do, must raise more to help more.

On the supply side, the “normal” donors (or “consumer donors”) who provide the bulk of donations to Europe’s non-profits are earning the same as they earned in 1998, or less. Perhaps this is part of the reason why regular fundraising has been struggling for so long; middle income donors (in Europe) have been taking home the same wages for the last ten years, so they are unable to increase their gifts, despite the best efforts of fundraising. As Prof Adrian Sargeant never tires of telling us,

‘In the UK, charitable giving is estimated to be around one per cent of gross domestic product and while there are annual variations, this figure has proved remarkably static over time. Despite the best efforts of governments, philanthropists and a generation of fundraisers, the needle hasn’t moved much on giving since data were first recorded.’

(Sargeant, A. & Shang, J., 2011. Growing Philanthropy in the United Kingdom. A Report on the July 2011 Growing Philanthropy Summit, Bristol, UK: University of the West of England. Available here.)

But up there among the elites the picture is very different. The top ten percent of earners enjoyed real-term income growth over the period 1998-2008 with the top 1% winning increases of 60% on average, world-wide. Yes, the subsequent recession may have taken a little off the top of that, but as the annual European wealth lists show us, wealth has survived the recession in remarkably good shape.

So at both ends of our work as fundraisers there is a case for strategic donors; at the poorest end where we have to do more and more for people with less and less, and at the wealthiest end where we can see a significant segment of the population heading up the income ladder.

Time to chase after your well researched prospect pool…with a strong, well-researched, case statement.

Which leaves me – and many fundraisers – in the ethical soup. I joined fundraising as a means to an end – the end of social inequalities, of poverty, of human suffering. So while I celebrate the growth of the strategic philanthropy market…I disapprove of the system that makes a few rich and leaves the rest poor.

Difficult dilemma.

But there is a lot of potentially philanthropic money out there, and a lot more people who need it; so stop wondering about major donors and get on with it.