In early 2017 Factary took the bold step to revolutionise the way we undertake Wealth Screenings. We launched our new Screening product in December 2017 and now, 16 months later, we have been able to reflect on the highs and lows of this process, and analyse the pros and cons of our new system. We thought we’d share our experiences here as they may prove useful to those who may be thinking of undertaking a Screening now or in the future.

Why did we change our approach to Screening?

To carry out our Screenings we used to hold a dataset of wealthy and philanthropic individuals (including data such as name, address, wealth analysis and data on professional / philanthropic interests for each individual). In 2017, in preparation for GDPR, like most other organisations we undertook full Privacy Impact Assessments (PIAs) on all of our products and services that made use of personal data. The PIA for Screening identified that, as the individuals held on our database were not aware that we were processing their data, and as some of the data would be deemed ‘intrusive’ (e.g. wealth analysis), our Screening posed clear risks to the individuals on the dataset (and, also, to us as an organisation and to our clients).

Ultimately, the PIA showed we had three choices: contact the individuals to ask for consent; attempt to justify the use of data under legitimate interests (and provide privacy notices to all the individuals on th/e dataset), or; stop Screening using this dataset entirely. We did not feel the first two options fully mitigated the risks involved to individuals, to Factary or to our clients, so (with the knowledge of the ICO) we decided to delete our dataset of wealthy and philanthropic individuals and start from scratch with a new Screening method.

Our new method

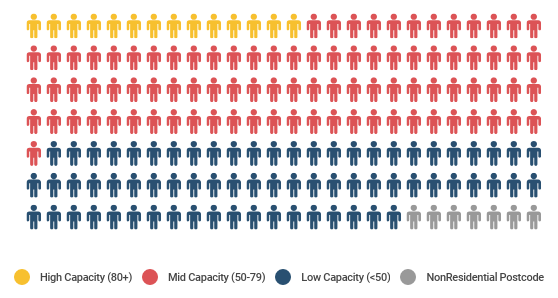

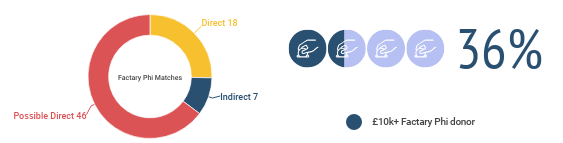

Full details on our new approach can be obtained by contacting us directly or reading more on Factary Screenings elsewhere on our website, but essentially we now make use of a number of data points to analyse a client dataset and identify those individuals likely to be major gift prospects. These data points include socio and geo-demographic data pertaining to 1.3m UK postcodes, bespoke and anonymised in-house wealth data points compiled from past Factary research, philanthropy data (to identify potential links to grant-makers & charities), and professional / business data (to identify links to top companies). None of this data is classified as personal data. We also make use of some datasets which hold names only, such as data from Factary Phi and some data from published Rich Lists. Alongside this, we make use of client data denoting connection or affinity (such as donation history, membership details, event attendance, ongoing relationships and much more) as our Screening approach doesn’t just focus on identifying the wealthiest amongst a support base but also those prospects likely to be warm to the cause or organisation.

So, does our new approach work?

We admit that this whole process was a bit of a gamble – it was a bit of a scary leap into the unknown and we had no real idea as to whether or not it would work (and we are very thankful to the small number of clients who helped us run pilot Screenings on their data in 2017 to allow us to review the outputs and efficacy of the new approach).

Thankfully, we are happy to report that the new process not only works, but is proving to be even more effective than our old approach. There are a number of reasons for this. Firstly, we are no longer relying on a static database of well-known individuals. We are now drawing from a variety of in-house datasets which has massively broadened the potential pool from which we can identify prospects and has naturally resulted in an increase in identified major donor potential.

Secondly, due to the new focus on demographic and occupational analysis we are able to identify wealthy individuals that would have previously been difficult to identify. This expanded focus, which is not reliant on prospects who are likely to be identified from static sources such as Companies House, has shown that we also now have a higher chance of being able to identify the very wealthiest prospects from professional sectors that were hugely underrepresented in our old approach (e.g. prospects with affiliations to investment firms or hedge funds).

Ultimately, this new approach to identifying prospects is more rounded and multi-layered which, when coupled with our bespoke analysis of giving history and affinity data, identifies a much wider range of wealthy and philanthropic individuals who can be prioritised not only by capacity to give but also by warmth/motivation towards the organisation or cause.

The cons

Of course, as with any process, it’s not fool proof. The new approach has its cons, too. For example, as one of the main drivers of our Screening is postcode data we are very reliant on clean address information in order to achieve successful results. Clients with out of date address data are unlikely to obtain the same results as those with clean data. That said, under GDPR we have found that many organisations have worked hard to ensure the data they hold is clean and accurate, so this is less of an issue than it might have been a few years ago.

Another slight downside is that not all individuals indicated as wealthy at the initial Screening stage can subsequently be identified from manual research in the public domain at the reporting stage, and for some we cannot confirm wealth. This means that a small percentage (around 17%) of identified prospects can ultimately not be included in the final reports. This does, however, highlight that our Screening involves a very careful process whereby an individual researcher reviews the results to ensure only relevant and verified major gift level prospects are included in the eventual pool (from a GDPR perspective this is important due to the process of justifying the type of individual that might ‘reasonably expect’ to be researched).

So, what are the typical results you can expect?

Given the pros and cons listed above, what are the typical results you can expect from the new Screening process?

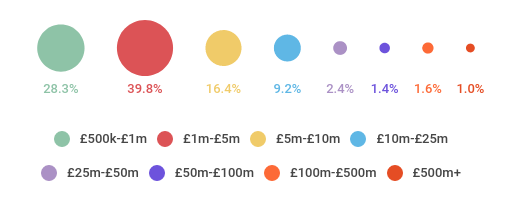

The overall breakdown of results (by wealth band) so far is shown below. This includes the percentage of prospects we have researched and verified at various wealth levels, after removing those prospects who cannot be identified in the public domain or who are not relevant for a major donor programme.

As can be seen, the results show a spread across levels of estimated wealth, with £1m-£5m being the most predominant (as expected) and then a more or less equal split between those with wealth of £5m-£10m, and those HNWIs at £10m+. As can be seen, our new approach also includes prospects with wealth of £500k-£1m (as, according to research, these prospects would have an annual gift capacity in the region of £5k-£10k, which easily puts them into a major giving category for the majority of our clients).

Unfortunately, it is difficult to use the data we have so far to provide an estimated breakdown of likely major donor potential (by wealth category) that can be identified from a ‘typical’ dataset as, predictably, the results do depend on the type of organisation we are working with, and the quality of the data we receive. For example, for one independent school we identified that 41% of the database had major donor potential (wealth >£1m), but as these types of datasets are likely to have an unusually high percentage of wealthy individuals it is not indicative of potential results more broadly.

However, results from numerous other charities (working in health, international development, arts etc.) so far show that the identification rate for >£1m prospects has been typically 3% – 5%. This is heartening as research undertaken in 2017 by Boston Consulting Group (BCG) showed that approximately 3% of UK households are millionaires. This indicates that our results mirror the wealth demographic in the UK but are also reflective of the fact that our clients typically segment their datasets to send us those prospects who are most likely to ‘reasonably expect’ to be researched (so their segmentations are likely to include a higher percentage of wealthy and philanthropic individuals than their wider datasets as a whole, meaning we may often identify >3% with major gift potential). Alongside this, because we also identify a relatively robust number of prospects at £500k – £1m, the eventual pool of potential prospects is typically quite broad for all of our clients.

These typical results also represent an increase in identified major gift potential when compared to our previous Screening results, which would, on average, identify 2.88% of a donor dataset (as was outlined in our ‘Guide to a Compliant Wealth Screening’ which can be accessed here).

TL;DR? It does work!

Ultimately, what this data has shown us is that our new process does actually work in identifying a broad range of potential major donor prospects for our clients, which is something of a relief for us! To have taken the bold move to stop using our in-house dataset was a daunting prospect for us, but to have found that not only could we continue to provide clients with a GDPR-compliant service to identify major donor prospects, but that it was actually even more effective than our old system has been very exciting. We are not resting on our laurels though – we are constantly reviewing and revising our processes to tighten up results so, hopefully, our Screenings will continue to improve in the coming months. Do please get in touch if you’d like to talk about the average results from your particular sector so you can see what the ROI from a Screening might be when translated into major gift potential for your organisation.

The GDPR bit…

…because what blog post about Screening would be complete without a GDPR section?

There are still a number of organisations in the sector who still ask if wealth screening is legal. The short answer is yes, it is. The longer answer is yes…as long as your organisation has met a number of requirements, which include:

Identify a condition for processing

You need to choose whether to rely on ‘consent‘ or ‘legitimate interests‘ to process data for wealth screening (you may find our previous papers on Legitimate Interest and Prospect Research and Factary’s Guide to a GDPR Compliant Screening useful in this regard).

Analyse your legitimate interests

If relying on legitimate interest (as, for example, 97% of higher education institutions are reported to be doing), the ICO outline that there are three elements to review, which are:

1. Identify a legitimate interest – what are the purposes for processing the data?

- Your organisation will need to be able to identify and demonstrate the reasons or purpose of undertaking a Screening. For example, you may outline that Screenings are used to identify those individuals from amongst a wider existing supporter base who may be able to offer financial support at a significantly higher level and to prioritise those who should be approached for a major giving programme

- It may also help to review the results of this academic study which provides evidence to support the use of research as an integral process in fundraising. For example, the paper shows that:

- 95% of fundraisers state that research enables them to identify relevant prospects

- 100% state that research is necessary for understanding prospects’ capacity to give

- 100% state prospect research enables their organisations to prioritise the prospect pool

- Of course, Screening also ensures that individuals who are not able to support you at a significant level do not receive irrelevant approaches from your organisation, which is another clear purpose of doing it. As evidence for this, the study cited above shows that 82% of fundraisers agree that research processes minimise the chance that inappropriate approaches are made to potential donors.

2. Show that the processing is necessary to achieve the purposes identified

- The ICO outline that data processing must be necessary and further state that if you can reasonably achieve the same results in a way that does not use personal data, then legitimate interests will not apply. Whilst our Screening does not use personal data we would still be processing the personal data held by your organisation, so this aspect of GDPR still needs to be analysed before a Screening is undertaken.

- The necessity of Screening can be evidenced by understanding how important major gift fundraising is to the continued success and operation of your organisation, including that major donors not only provide financial support but also contribute in other, less tangible ways, such as bringing expertise, skills and their professional or personal networks to provide support and guidance to non-profits (Eberhardt S & Madden M (2017) Major Donor Giving Research Report. London: NPC).

- Screening is typically the first step in major gift fundraising as it enables you to identify relevant prospects for a programme in an efficient, cost-effective and accurate way.

- Other methods for identifying relevant major gift prospects were reviewed in the academic study outlined above, including data mining / segmentation (such as analysing a donor or alumni database to identify those who are making abnormally large or out-of-pattern gifts, or from modelling their dataset to identify individuals with similar characteristic to their major donors), or from sending questionnaires to constituents on a database and asking for details on salary / professional info etc. Results from the study (see page 22 onwards) showed that the vast majority of fundraisers felt that, even if organisations undertake other methods then prospect research processes would still be required in order to, for example, identify sufficient numbers of major gift prospects.

- Using the type of evidence and arguments outlined above, you can prove that Screening is necessary and that the results from Screenings cannot be achieved by using other methods.

3. Balance the processing against the individual’s interests, rights and freedoms

The ICO state that you must balance your need to undertake processes such as Screening against individuals’ interests. If the individuals would not reasonably expect the processing, or if it would cause unjustified harm, their interests are likely to override your legitimate interests.

- It is important, therefore, to be able to explain / evidence that activities such as Screening do not have a disproportionate impact on individuals. Our paper on Legitimate Interest and Prospect Research contains an overview of the type of processes to go through, the questions to ask and the evidence that can ultimately be gathered in order to do this (see page 15 onwards).

- Additionally, we recently conducted a study into privacy notices which can be accessed via our blog. This provided very clear evidence that, when individuals are contacted to be informed that organisations are undertaking Screening (by receiving a privacy notice), very (very) few of them react negatively. For example, as the blog shows, only 0.0000411% of (almost 2.5m) individuals chose to opt out of their data being used in prospect research when given the opportunity. This, as we outline in the blog, “…provides an evidence base that can be used to argue that the balancing exercise carried out by non-profit organisations to review individuals’ interests, rights and freedoms was fairly judged because, if it hadn’t been, then presumably the number of individuals complaining about or opting out of prospect research would be significantly higher”.

4. Transparency:

One of the 7 principles of the GDPR is ‘lawfulness, fairness and transparency’. Some of the processes outlined above will ensure you are meeting the standards of lawfulness and fairness required for this principle, but adhering to ‘transparency’ is vital – particularly when it comes to Screening as a lack of transparency formed the basis of the ICO fines to charities for Screening in 2016.

- Transparency is achieved through the provision of a clear and concise privacy notice. Plenty has been written about how to write a good privacy notice and what to include but there are now some great examples of privacy notices which include Screening in their scope (see here and here).

- If you do not provide individuals with a privacy notice your organisation cannot claim that it has upheld the rights of individuals (as required under the GDPR), specifically those such as the right to be informed, the right to restrict processing or the right to object to processing.

- Incidentally, this principle formed the basis of Factary’s decision to delete our database of wealthy individuals that we used to hold for Screening as our PIA showed that we did not allow individuals to exercise their rights (as they had not received a privacy notice from us outlining the reasons for which we used their personal data).

The four elements described above that need to be reviewed/worked through in order to undertake a compliant Screening may feel slightly onerous, but they are imperative if your organisation wants to move forward with any type of data processing for fundraising.

Further discussion

If you’d like to chat about Screenings, or how to approach undertaking a DPIA or analysing the GDPR requirements around Screening then please do get in touch.