Welcome to the September 2013 issue of the Factary Phi Newsletter.

Major Giving News

London Business School to receive £10m

Nathan Kirsch has donated a whopping £10m to help top up the endowment of London Business School, raising it to just under £36m as a result.

The South African businessman, who also purchased London landmark ‘Tower 42’ in 2011, has offices and a home in London located close to London Business School. However it was through his daughter that they first came into contact after she received her MBA in 2012.

Speaking on his donation, Mr Kirsch noted that American schools ‘have a much more active alumni stream in money-raising and promoting the university,’ adding that his £10m is intended to create a ‘benchmark’ for others to ideally follow on from.

London Business School’s Dean, Andrew Likierman echoed this sentiment, ‘Having set the example, the intention is to ask others to continue in the same way’ adding that ‘There are enough big companies floating around to be able to do this … British companies and companies that do business in Britain’.

According to Prof Likierman, the money will be used to increase the quality of both the teaching and the research at the school, with the aim of ultimately attracting more top students.

H&M raises £1m for charity

Clothing retailer H&M have raised £1m for charity through the sale of end-of-season stock.

In a partnership formed with the British Red Cross, the company have donated almost 330,000 clothing items and accessories to be sold in 325 charity shops over a two year period.

Paul Thompson, head of retail at the British Red Cross, said: ‘We are really thankful to H&M for helping us to give our customers even greater choice. The donated items we’ve received are bang on trend and this means we can continue to attract younger customers to our stores, offering them fashionable clothes at a great price, which is really important.’

The money raised will go towards supporting the British Red Cross in its work both at home and overseas in places such as Syria and West Africa along with the UK.

H&M will also continue to donate unsold stock to charitable causes, which would otherwise have gone to landfill sites.

Dorchester hospital gets £50,000

The Friends of Dorset County Hospital have donated £50,000 towards the development of its specialist dementia ward.

The ward, which has done much to improve the support offered to patients, has already had its day room refurbished to look like a lounge and dining room from the 1950s, complete with vintage furniture and fittings and authentic household appliances such as a television and radio.

The money from the Friends will be used to remove the central nurses’ station to create a seating area for patients, create clearer signs and colour coded walls, railings and doors to guide patients around the ward and add to the day room. Portable touch and sensory equipment will also be purchased to help patients who are bed bound.

Speaking on the donation, Healthcare Assistant Samantha Watt who runs the Memory Lane Room, said she and her colleagues were extremely grateful for the Friends’ funding, adding that ‘The nurses’ station can be intimidating and confusing for patients so removing that will make a big impact and we are going to make it much easier for patients to identify the different areas of the ward. We’ll also be able to refresh the Memory Lane room which is fantastic. We can’t thank the Friends enough.’

Friends Chairman John Weir said they were delighted to be able to fund these improvements: “We do feel that dementia is an underfunded area generally and there’s a growing need. The Barnes Ward team have already done a great deal for patients and we are really pleased to help them further improve the care and support for elderly people coming into hospital.’

Report: On the Money

For this month’s edition of our report section, we have included our summary of a recent report on how third sector organisations think about money, along with some analysis on how this affects different organisations in the way they operate.

The full report, which is entitled ‘On The Money’, draws upon an earlier piece of research entitled The Third Sector Trends Study, and was written Fred Robinson and Tony Chapman of Durham University.

The research was commissioned by the Northern Rock Foundation.

Introduction and Summary

The report begins by acknowledging the fact that that for many third sector organisations (TSOs), attempting to secure adequate funding can often feel ‘like an all-consuming pressure’, especially when they are faced with the burden of maintaining an adequate service, while at the same time battling to keeping valued employees in their jobs.

This is frequently the case for many larger TSOs, as it is often these organisations that depend the most heavily on maintaining a steady stream of funding in order to keep their services afloat. Therefore, it is these larger types of TSOs that are the main focus of this report.

In the present financial climate, it is often considered the norm for a large number of these organisations to experience some substantial fluctuations in their income, which in turn leads to a great deal of uncertainty. In the face of this, a relentless search for money by many TSO’s can start to become an end in of itself, regardless of their financial position, healthy or otherwise.

This approach, it is argued in report, can be highly detrimental to the end goals of any TSO, as simply ‘throwing money’ at an unresolved issue does not guarantee a solution, and may in some situations be part of problem. Although undeniably important, money should be considered a ‘medium’ through which, amongst other things, other organisational objectives can be achieved.

In an ideal world, practical and efficient TSOs should be able to spot and utilise a source of income in order to achieve their objectives, and furthermore, they should also be able to recognise when an income stream has the potential to harm or hinder their organisation in achieving its aims.

It is argued that this sense of ‘organisational foresight’ must always be present so that TSO leaders can accurately weigh up the ‘opportunity costs’ of making decisions. This means considering and having a clear understanding of the potential risks associated with making big decisions. For TSO’s to be enterprising, it is argued, it is not just about getting the money in - it is also about knowing what the purpose of that money is in relation to the organisation’s social objectives.

Furthermore, it is also considered highly important for TSOs to stay true to their original mission as much as possible, rather than focusing too heavily on pursuing funding opportunities above their other objectives.

The Meaning of Money

It is important to remember that TSO’s also receive money in a number of different ways. For example, the value of earned money is articulated quite different from gift money. TSO’s may even make use of borrowed money in some situations, although this is less commonplace. It could for example be involved in a payment by results programme, whereby working capital may be required to provide cash flow to bridge the gap between the costs of programme delivery and payment for services rendered.

Comparatively, for private sector organisations considerations about the value of money are much less cluttered. This is because there is no need for them to draw distinctions between gift money and earned money.

For TSO’s, different sources of money and income can be categorised in a number of different ways, some examples include:

- Given money (grants, gifts, endowments etc);

- Earned money (through the delivery of contracts, through trading or via investments); or,

- Borrowed money (to provide investment capital, working capital, etc).

However, it is noted in the report that these distinctions are only rarely drawn and for the most part, all money is broadly discussed as ‘funding’.

How is money valued by TSOs?

As is demonstrated above, the money used by TSOs may come from a variety of different sources, however according to the research, the word ‘funding’ was found to be the most popular and emotive term. This section explores the extent to which the ethos of TSOs may affect the way that they think about different sources of money.

In a TSO1000 survey conducted earlier in 2012, respondents from the sector were asked which sources of ‘funding’ were of most value to them. Respondents could assign the values ‘most important’; ‘important’; ‘of some importance’; and, ‘least important’ to different sources, and they were also given option of explaining that the source of money in question was not applicable to them, depending on their organisation.

Furthermore, they were also given a second question to answer referring to organisational ethos. This was: ‘Where do you think your organisation sits in relation to the following’. Respondents were then presented with a series of issues to respond to, and were given the option of ticking ‘people in the public sector’, ‘people in the private sector’, and ‘people in the community’.

According the results of the survey, the majority of respondents position themselves most closely to ‘people in the community’ in relation to all of the value based questions. The data shows that:

- About 20-25% of TSOs, no matter what their practice ethos is, did not perceive gifts to be applicable them.

- TSOs with a community sector driven practice ethos were less likely to perceive that in-kind contributions were applicable to what they do (which may seem odd, given their likely reliance on voluntary support) compared with about 28% of other TSOs. 70% of these TSOs did not regard contract work as being applicable to them, half felt the same about earned income or investment income, and 90% about loans. Perhaps surprisingly, 43% did not think that subscriptions were applicable to their organisation and 25% felt the same about grants.

- Only 16% of TSOs with a public-sector driven practice ethos did not regard grants as being applicable to what they do; around 35% felt the same about contracts or earned income; about half had no apparent reliance on investment income; and, 64% had no income from subscriptions. Loans were apparently not applicable to the majority - 85% said this kind of money was not applicable to them.

- The TSOs with a private sector driven practice ethos differ in some respects from other TSOs - but these differences are not large. They were less likely to say that earned income was not applicable to what they do (32%). Only 22% considered that loans were applicable to what they do.

- TSOs with a community or public-sector driven planning ethos were far more likely to place high importance on grants (around 55%) than those TSOs with a private sector driven practice or planning ethos (just 40%).

- TSOs with a public or private sector driven practice or planning ethos were much more likely to place high importance on contracts or SLAs (around 55% compared with about 35% of TSOs with a community driven practice or planning ethos).

- Earned income was most important in TSOs with a private sector driven practice ethos (53%, compared with 42% with a public-sector driven practice ethos). Only 20% TSOs with a community sector driven practice ethos, by contrast, said that earned income is of high importance.

- Investment income was of high importance to TSOs with a community driven practice or planning ethos (25%) followed by private sector driven ethos (17-21%) and public sector ethos (12%).

- In-kind contributions were less important to TSOs with a private sector driven practice or planning ethos (about 10% say it is highly important) compared with other organisations (between 18-23%).

- Gifts were of less importance to TSOs with a private sector driven planning and practice ethos (about 21-22% stress high importance). About a third of other TSOs emphasise the high importance of such sources of income.

- Subscriptions were more likely to be of high importance to TSOs with a community driven practice and planning ethos (around 47%) compared with other TSOs (private sector ethos TSOs being the least reliant on such sources of income).

- No TSOs with a public-sector driven practice and planning driven ethos placed high importance on loans. About 14 - 17% of TSOs with a public-sector driven practice or planning ethos, by contrast, said that loans were of high importance to them.

Based on the survey’s findings, it is argued that concentrating on money alone is unlikely to help TSOs achieve their aims. This is explored more fully in the next section.

Getting it right

When a TSO’s income rises substantially (possibly due to winning a grant or contract, or due to the receipt of a legacy for example) the organisation may also have to consider how to manage any surplus money it has available.

In some situations this money could be saved, invested in its staff, or possibly even used to scale up the size of its operations in the long term. However crucially, this would only be done if there was a realistic prospect that such a position can be maintained, and its operational objectives fulfilled according to its mission statement.

In contrast, when TSO’s experience a significant fall in income, decisions are made on what to do while maintaining a position of healthy equilibrium for the organisation. It could for example bring in extra money to quickly fill a gap, or alternatively, the TSO might decide to adjust its long term position and as a consequence, restructure its operation to meet these challenges.

According to the research’s analytical framework, the TSO would ideally:

- Have the foresight to be able to scan the horizon for medium and long term opportunities and be mindful of how much it wishes to hold to or adapt its mission to achieve good outcomes for its constituency of beneficiaries.

- Be sufficiently enterprising to assess the risks associated with positioning itself appropriately to capitalise on new opportunities - which may or may not involve working with other organisations.

- Understand what its level of capability is now and know what potential there is to increase its capability in future to meet the needs of new operational challenges.

- Know what the organisation is there to do and be able to recognise what impact their work achieves for beneficiaries.

Getting it wrong?

When a TSO does not respond well to receiving a substantial amount of money, it can lose sight of its original position and fail to properly assess the opportunity costs of growing too fast. The new challenges it faces could for example badly dent the motivation and morale of its employees, or as a result of such rapid growth, the TSO may become unable to carry out its work with the same level of dedication and skill that is required.

The consequences of this can be disastrous, as without a proper sense of equilibrium that allows the TSO to be mindful of its original values, it can also exaggerate the impact of a steady or sudden decline in its income.

Based on the research, the following brief observations were made on how things may go wrong for such organisations. The TSO:

- May know how to scan the horizon for short-term opportunities - but not in line with its own mission or capability

- Does not know when to and not to engage in activities - but grab things they have limited interest or capability in doing

- Is not fully aware of its own organisational assets (of people, resources and ideas) nor of its own potential for development

- May be confused about the beneficiaries they are there to serve and don’t know what difference they make because they over prioritise organisational survival

These examples do project some rather ‘extreme’ responses to uncertain situations, and it is noted in the report that it is of course impossible for an organisation to perform perfectly at all times. Indeed, even the most well governed and organised TSO can suffer some periods of bad luck, no matter how well they prepare for future possibilities.

However, the irony is that some TSOs which are closer to the ideal type of the ‘well governed’ organisation may suffer periods of bad luck no matter how well they prepare for all future possibilities.

Conclusions

The report argues that overall, it is a commonly held expectation that TSOs ‘should be funded in order to do their good work’ rather than to simply find a way to ‘get the money in to get the job done’. Based on the research, it is argued that well governed TSOs should attend to issues surrounding key organisational objectives first, and then consider money second. Money, in short, should always be considered as a medium (but not the only medium) for getting things done.

Furthermore, it was reasoned that in order to avoid the pitfalls of TSO’s overstretching their resources, good governance with a clear sense of organisational foresight is always necessary in order to anticipate the outcomes of important decisions. To this end, TSO’s must maintain a high standard when assessing the potential risks involved with taking on more resources and new projects. It is thought that if money is brought in to do something the TSO is self-evidently ill-equipped to achieve, it can easily cost the organisation more than the value of the money brought in.

The success of a TSO should be based on a clear sense of organisational identity and good governance rather than by placing importance on money or its income stream. Although money is undeniably important for TSO’s in order to effectively achieve their goals, a balance must be struck that attends to both the needs of the organisation and also achieves good outcomes for its beneficiaries.

Clickhere for a full version of the report.

Phi in Numbers September 2013

During the course of this month we have uploaded 8,220 new records of donations onto the Factary Phi database, bringing us to a grand total of 441,819 searchable records.

The data in the latest upload has been taken from a number of different organisations, including the Shakespeare Globe Trust, Opera North, The National Gallery Trust, The Southbank Centre and more, all of them operating within the Arts/Culture sector.

From these 8,220 new records, there are 6,061 donations from individual donors, 323 of which have been made by titled individuals to various causes (this includes Lords, Ladies, Sirs, Viscounts, Dames, Honourable, Earls, Dukes, Barons, Counts & Countesses).

In light of this, we have decided to do some analysis on donations made to this sector by titled donors, and in particular, how donations made from titled individuals compare across the different activity types in Phi.

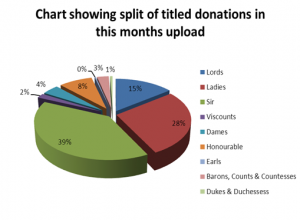

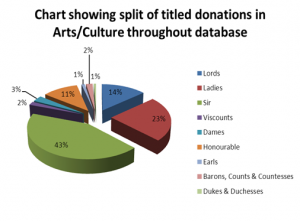

The pie chart below shows the percentage split of donations from titled individuals in this month’s upload, and alongside, the second chart shows how they are spread across the entire database.

As is demonstrated by the chart, this month’s upload is fairly consistent in terms of donations from titled donors, although there is a slightly higher proportion of donations in the Lords, Ladies, Dames and the Honourable categories.

Overall, it is interesting to note that the Arts/Culture activity type contains 1,691 records of donations from titled individuals, as this makes up a substantial 56.63% of the database in terms of titled donations to all activity types. Below, we have also included a chart showing the breakdown of donations from titled individuals to all other activity types (excluding Arts/Culture donations) across the database.

Profile: The Leverhulme Trust

The Leverhulme Trust was established in 1925 according to the will of the First Viscount Leverhulme with the intention of supporting charitable causes associated with research and education in the UK.

A Victorian businessman and entrepreneur, William Lever began his career working for his father’s grocery business in Bolton, before eventually became a junior partner in the company by 1872. However, it was not until later in 1885 that he would found the highly successful soap and cleaning products company, Lever Brothers, with his younger brother James. The company was among the first to manufacture soap from vegetable oils, and under his leadership it produced a great fortune, eventually selling soap brands in 134 different countries.

The business expanded rapidly, and as time went on William Lever also became heavily involved in British politics. A lifelong supporter of William Ewart Gladstone and Liberalism, he was invited to contest elections for the Liberal Party during his later years. And as well as this, he also served as Member of Parliament for the Wirral constituency between 1906 and 1909, notably using his maiden speech in the House of Commons to urge Henry Campbell-Bannerman’s government to introduce a national old age pension, such as the one he provided for his workers.

After being recommended by the Liberal Party, he was then created a baronet in 1911 before eventually being raised to the peerage as Baron Leverhulme in 1917, and finally to the Viscountancy on 27 November 1922.

After his death in 1925, he left a proportion of his shares in Lever Brothers in a trust for certain trade charities and also for the provision of “scholarships for the purposes of research and education”, thus establishing the Leverhulme Trust.

Today, his foundation still supports a variety of charitable causes associated with research, education and the arts with an annual funding of around £60m, making it one of the largest providers of research funding in the UK.

For the financial year ending 31st December 2012, the trust reported an income of £64,157,000 and an expenditure of £75,002,000. Factary Phi holds 138 records of made between 2005 and 2012 worth a minimum of £34,570,702.

From these, the highest single donation was made to the Royal Society for £3,620,000. In terms of average grant size, the largest are typically made to causes associated with Education/Training (£607,588).

According to Phi, the largest number of donations have also been made to causes associated with Education/Training (76), followed by Arts/Culture (57) and finally Animals/Environment (5).

The Trustees

Sir Michael Perry

Sir Michael Perry GBE is a former Chairman of Unilever plc and Vice Chairman of Unilever NV. He is currently a Director of Singapore Technologies Telemedia Pte Ltd, a Trustee of the Dyson Perrins Museum Trust, Chairman of the Leverhulme Trust and Chairman of the Leverhulme Trade Charities Trust. Prior to this, he has held senior positions in a number of different companies, including as Chairman of Centrica plc, Chairman of the Dunlop Slazenger Group Ltd, Deputy Chairman of Bass plc and as an executive Director of Marks & Spencer plc.

Dr Ashok Ganguly

Dr Ashok Ganguly spent much of his career working for Hindustan Lever Ltd and from 1980 to 1990 he served as its Chairman until the end of his 35 year career with the company. As well as this, he has also held a number of senior positions with other multinational companies, including ICI India, British Airways, Wipro, Tata AIG Life Insurance Co, Hemogenomics, and Firstsource Solutions. He is also a Trustee of the Leverhulme Trade Charities Trust.

Niall Fitzgerald KBE

Niall Fitzgerald KBE has also held various positions with Unilever plc and has worked for the company for 30 years. Until May 2011 he was Deputy Chairman of Thomson Reuters and he recently worked as a Senior Advisor with Morgan Stanley International. Prior to this, he has held a number of positions with Unilever plc during his 30 year career, including as Finance Director, Foods Director, Detergents Director and also as Chairman and Chief Executive Officer until his retirement from the company in 1996. He is currently a Trustee of the British Museum Friends and the Leverhulme Trade Charities Trust.

Patrick J P Cescau

Patrick J P Cescau is a Senior Independent Director of Tesco plc. Prior to this, he was a Non-Executive Director and later a Senior Independent Director of Pearson plc, a Group Chief Executive of Unilever plc until 2009 and he has also held the position of Chairman, Vice Chairman and Foods Director of Unilever NV. Cescau was also a Non-Executive Chairman of InterContinental Hotels Group and a Non-Executive Director of the International Airlines Group. He is Chairman of St Jude India Children’s Charity.

Paul Polman

Paul Polman is Chief Executive Officer of Unilever plc and prior to this, he was Chief Financial Officer and head of the Americas with confectionary group Nestle and he has held a number of senior positions with consumer goods company Proctor & Gamble.