Welcome to the September 2014 issue of the Factary Phi Newsletter.

Major Giving News

John James Bristol to donate £500,000

The donation has been made as part of a campaign to transform two Bristol hospitals.

A total of £3m has been raised so far, and the money is to be spent on a new Bristol Haematology and Oncology centre, allowing adult cancer patients to be treated under one roof.

Julian Norton, who is chief executive of the foundation, said ‘We have had a lot of involvement over the years with the hospitals.’

‘We have always been quite health focused, we funded one of the first MRIs at the hospital. I’m very pleased we have donated half a million because I know how needed it is.’

‘We always hope donations like these will help to release funding from elsewhere as well.’

Canadian bank donates half a million to UK charities

The Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce is set to donate more than £650,000 to three children’s charities in the UK.

The donations, which are to be made through the CIBC’s Children’s Foundation, are to go to CHICKS, PACE and finally the Honeypot Children’s Charity, all of which are based in the UK.

Speaking on the donation, Kevin Li, who is CIBC’s Managing Director said ‘We are pleased to support these charities and their programs which offer long-lasting benefits to so many.’

The bank’s donation comes as part of the company’s 30 year anniversary, which marks the creation of the CIBC Children’s Foundation. Since its inception, £138m has been raised globally towards causes associated with vulnerable children around the world.

This year is the 30th anniversary of the creation of the CIBC Children’s Foundation, established in 1984 to raise funds for children’s charities around the world. Since inception, £138 million has been raised globally to improve the quality of life of thousands of children affected by disability, illness, social deprivation or life-limiting conditions.

Child Cancer Fund to receive £1m

Through her personal foundation, Dame Margaret Barbour is set to donate £1m to The Future Fund, a children’s charity currently aiming to raise money for a new state of the art cancer research centre at Newcastle University.

Dame Barbour, who is Chairman of South Shields-based global clothing brand of the same name, announced the major gift at a recent fundraising event in Newcastle.

Speaking on her donation, she said that (the) ‘Treatment of childhood cancer has been one of the success stories of modern medicine, but there is still further progress to be made. The Future Fund campaign will enable this progress to move on to the next level. I am extremely proud to be associated with this vital work.’

The donation brings the total raised by the Future Fund to £1.7m since its launch just 11 weeks ago and endorsement from North-East heroes including Sting and Mark Knopfler.

Report: ‘Closing in on Change’

This month, we have included our summary of a recent report on campaigning among charities, conducted by Cecilie Hestbaek on behalf of the NPC.

The report is entitled Closing in on Change, and more specifically, it discusses how effectively charities measure the impact of their campaigning strategies and how this might be improved.

Introduction

The report begins by acknowledging the fact that most charities do measure the extent of their impact in some way, as this has arguably become an integral to their work, and because it is also driven in part by the their own funding requirements. However, this approach is not wholly evident across all parts of the sector. In particular, some conversations with campaigning charities have revealed that that many do not measure the impact of their campaign, because they appear to lack the time and expertise, or simply because they doubt it will be of an appropriate benefit to their work.

This report argues that this is an essential measure that should not be overlooked, as this evaluation allows charities to better demonstrate their achievements and learn how they can improve.

What is Campaigning?

Put simply, a campaign aims to target decision-makers in order to achieve high level change. This is defined by NCVO as:

‘Organised actions around a specific issue seeking to bring about changes in the policy and behaviours of institutions and/or specific public groups, (…)the mobilising of forces by organisations and individuals to influence others in order to effect an identified and desired social, economic, environmental or political change.’

The relationship between service delivery and campaigning is often compared with one between symptoms and causes. For example, a service can be used to help relieve the symptoms of an individual’s problem, but this will rarely affect the circumstances that are the root cause of the problem in the first place. Campaigning strategies themselves, it is argued, can be used to address the fundamental causes behind a particular issue, such as the structural factors affecting homelessness, or the social welfare concerns that might be caused by the planned closure of a hospital.

Campaigning Activities and Objectives

Campaigning activities and objectives can be very diverse. Therefore in this paper, the research distinguishes between two main types of objectives: Policy Influence and Behaviour Change.

According to the report, the first is more concerned with changing or protecting existing policies, while the second is concerned with changing the behaviour, either of the public, or of specific groups in terms of their attitudes, opinions or actions:

- Policy influencing campaigns employ a range of different tactics – from advocacy and lobbying work to research, advice and recommendations for policy context or processes, and direct action/activism, including demonstrations or mail petitions.

- Behaviour change tactics can overlap with policy influencing methods if they target policymakers or civil servants, for example.

Measuring the Impact of Campaigning

While campaigning can undoubtedly prove to be a powerful tool in bringing about social change, the point is made that this can be a risky pursuit for many charities, as the process will often involve the expenditure of scarce resources that charities might not necessarily have ready access to, and despite the risk, their success is still far from guaranteed. Measuring the impact of this work can really help raise confidence when pursuing a particular campaign, and it can also help charities ascertain whether or not their strategy will remain viable for them in fulfilling their goals.

Trustees are legally bound to spend resources in the most effective way possible, and a good evaluation framework will allow charities to monitor whether or not their campaign ultimately lives up to this promise. Some of its advantages include:

- Learning on the job. Campaigns are often quite complex and long term. They can for example involve a range of ‘tactics’ that run in parallel, and understanding which of these are most effective can be subject to change as time goes on. These need to be continually assessed, and placing them within an evaluation framework can help charities to proceed in a more structured and evidence based way.

- Accountability to stakeholders. In some circumstances, campaigning can risk your charity’s reputation. Therefore for this reason, it is important to explain the causal links between your tactics and the social change that the campaign aims to bring about. Reporting on this to members, funders and beneficiaries will make it easier for them to understand the big picture.

- Appealing to funders. Funders increasingly want to see more evidence of impact as a growing number of them become more strategic in their approach. Therefore, demonstrating how a particular campaign is successful will help attract funders and allow them to monitor their own impact.

Challenges

This evaluation is not always a simple process, some challenges include:

- Output versus outcomes. A charity’s output is often easier to focus on than the outcome itself. For examples the number of events held, or the number of leaflets handed out could be used as proxy indicators. However, the effectiveness of a campaign can only truly be measured if you can evidence the link between those events and leaflets in relation to an immediate or final outcome.

- Causality, consistency and predictability. Linking campaigning and outcomes is complex, for example the same activities for two different campaigns may generate two completely different outcomes depending on the external environment.

- Time frame. As the time frame between different campaigns can vary so much, it is essential to ensure that the effects of the campaign are still forthcoming. Developing a measurement framework with intermediate outcomes can help charities to better track their progress.

- Contribution and attribution. When discussing campaigns, it is important to remember that there are a variety of external factors that can influence their success, and many of these factors can often be beyond a particular charity’s control. Because of this, it can sometimes be difficult to accurately assess the effectiveness of a campaign. Therefore in campaigning work, it is important to demonstrate that you have at least made a contribution to change.

- Data collection. Sometimes, it can be difficult to collect data from the people you are aiming to influence, and this can be even harder if you are attempting to target top-level decision makers.

The Four Pillar Approach

First published in June 2014, a ‘four pillar approach to measurement’ was devised in order to provide guidance for charities in developing and implementing an impact measurement framework. This approach is intended to help other organisations understand and improve their activities as well as report on their progress. These steps are summarised below:

Step 1: Map Your Theory of Change

When measuring the impact of a campaign, it can be difficult for many organisations to even know where to start. Creating a theory of change can help you to prioritise what, and how to measure in a systematic way. If there are causal links between intermediate and final outcomes that are well evidenced, then it is reasonable to expect that these final outcomes will occur.

Step 2: Prioritise What you Measure

When collecting data for a campaign, gathering in an ad-hoc, opportunist way may seem like the most convenient option. However, it is important to remember that in any campaign, collecting the right amount of quality data is key to a good evaluation. In some circumstances, it may also be worth collecting data on the possible negative or unintended consequences of a campaign, as an awareness of these factors will allow for better preparation on the future.

Step 3: Choose Your Level of Evidence

Before deciding on exactly how to collect data, it is first important to determine how rigorous and credible the evidence needs to be. It should suit the needs of different stakeholders, as well as your own particular resources and capabilities, bearing in mind the importance of focusing on the quality and accuracy of measuring the date itself before quantity.

Funders often push less for solid evidence of impact in campaigning than in other areas (or, if they want solid evidence, they stay away from campaigning). This does not mean it shouldn’t be provided however, when measuring impact charities need to choose a level of evidence that is proportionate to the size of the campaign itself, so that the evidence and data can be collected realistically depending on their resources.

Step 4: Select Your Sources and Tools

Once an appropriate level of evidence has been decided, it is important to consider exactly what data to collect, and then develop the appropriate measurement tools or data sources to capture it. Ideally, some of the casual links towards the campaign’s ‘end goal’ will be supported by existing evidence-whether your own work or produced by other organisations or academics. The most important measurement tools need to be fit for purpose and capable of capturing appropriate evidence of the change that you wish to bring about with your campaign.

Conclusions

This paper was developed in order provide a step by step response to the increasingly complex campaigning environment felt by many charities. Based on the research, the current environment calls from an increased sense of clarity from campaigners in their approach to their strategies, achievements and overall goals. The NPC’s four pillar approach to measurement can be applied to campaigning work, drawing additionally on the useful tools and guidance developed by organisations such as the NCVO and ODI and while the work of measuring the impact of influencing, advocacy, or behaviour change work can seem extremely complex, the right step-by-step approach can be achieved even while the campaign itself is being carried out, which is something that can be of a huge benefit for organisations both in terms of their learning and effectiveness.

Clickhere for a full version of the report.

Phi in Numbers September 2014

The annual publication of a Giving Index by the Sunday Times, whilst not perfect, is quite possibly the best measure of overall UK philanthropy available. Phi contains records of all those individuals, couples and families that have appeared on the index between 2007 and 2014, giving some insights into those who have been arguably most philanthropic over that period.

The data shows that there are actually only 356 rich list entrants who have appeared on the giving index over this period – with most making multiple entries. There is a particular group of 24 “super philanthropists” who have appeared on all eight of the lists. They include high profile names such as David & Heather Stevens, Elton John, George Weston, Hans Rausing, Jack Petchey, J K Rowling and Lord Sainsbury.

The total amount of donations recorded by the index over this period is in excess of £17.5bn – making an average of £49m per identified donor over the total period or £6m per donor per year.

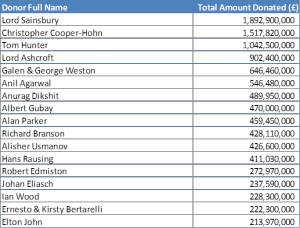

It is clear from these averages that a small number of donors are contributing at significantly above the average rate. Those who have donated in excess of £200m over the period according to the Sunday Times are:

However, it is also noticeable that as many as 43% of those featuring on the Giving Index have donated less than £5m over the period in question – at least in terms of the donations featured by the newspaper – which makes the picture look rather less generous. Amongst these 155 donors, the total amount donated is only £252m – an average of £1.6m per donor or £203,000 per donor year.

The median donation amount seen amongst those appearing in the Giving Index is actually £7.5m over eight years or – rather neatly as this is a figure that we might hope to see – just under £1m per year.

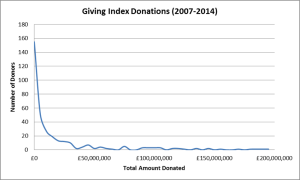

The bias towards this more “normal” level of major donation is perhaps illustrated by the chart below. This shows number of Giving Index Donors at each £5m donation level up to £200m and suggests that lifetime donations in excess of £50m are still the province of a very select group.

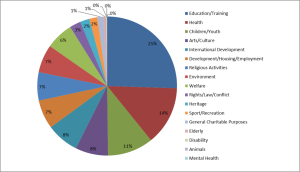

Education & Training emerges as the clear preference for philanthropic investment by rich list entrants with an estimated 25% of donations going to this sector. The three sectors of Education, Health and causes related to Children/Youth together account for an estimated half of Giving Index donations. Mental Health, Disability and Animal related causes (other than those with wider Environmental concerns) appear not to be favoured.

Methodological Notes:

- Analysis is based on all Phi entries with a Recipient Name of ‘Various’.

- Although every effort has been made to identify them, variations in naming conventions across the years (eg use of nicknames, names quoted with/without spouses, with/without title, in differing orders etc) may have led to some repeat entries being missed.

- Equal allocation of funds across listed Activity Types has been assumed – this may, of course, not be accurate.

Profile: John Lyon’s Charity

Originally created in 1991, this foundation was formed from the endowment of John Lyon, who was a yeoman farmer from the village of Preston in Harrow.

Born in the 16th century to John Lyon and his wife Joan, he was a wealthy and educated landowner who at one time had the largest rental in Harrow. This wealth he accrued during his life allowed him to support his local community in a number of ways, and this influence has continued into the present.

Firstly, he was able to endow the local Harrow School, which led to the creation of The John Lyon School, named in his honour, and he also established a trust for the maintenance of Harrow Road and Edgware Road. However, as these roads are now maintained by the local council, this income from his estate is instead used to provide various charitable projects in the Harrow area with funding.

In 1571 he bought lands in Marylebone for the purposes of education, and the following year in 1572, he also obtained a charter from Queen Elizabeth allowing him to found a free grammar school for children. The land was to be held by himself, his wife, and the governors of his school. Also this period, a £50 levy on his lands was proposed as a loan to the state, however the attorney-general, Sir Gilbert Gerard interposed on his behalf, successfully arguing that he should not be forced to sell any lands he purchased for the maintenance of his school.

The John Lyon’s Charity in its current form was realised in 1991, when a Charity Commission scheme came into effect allowing the Governors to apply the income from his endowment for the benefit of the inhabitants of Barnet, Brent, Camden, Ealing, Hammersmith & Fulham, Harrow, Kensington & Chelsea, and the Cities of Westminster and London. In keeping with its founder’s original interests, education causes and children remain the charity’s main funding priority.

For the financial year ending the 31st of March 2013, the trust reported an income of £6,755,000 and an expenditure of £7,289,000. Factary Phi holds 103 records of donations made to various organisations since 2006 worth a minimum of £5,964,435.

According to Phi, the average size of donations made by the trust is £34,879 and the largest proportion of these donations have been made to causes associated with Arts/Culture (107), followed by Education/Training (46), Children/Youth (24), Sports/Recreation (17), Welfare (16), Development/Housing/Employment (10), Health (6), General Charitable Purposes (6), Disability (6), Rights/Law/Conflict (5), Environment (3), Heritage (2), International Development (1), Mental Health (1), Religious Activities (1).

The Trustees

Andrew Stebbings

Andrew Stebbings is Chief Executive Officer of the charity, and he is also a Partner with law firm Pemberton Greenish LLP. He is a trustee of the Harrow Club, and he has previously held positions as Chairman of the Royal Masonic Trust for Girls and Boys and a Partner at Lee & Pembertons. He attended New College, Oxford.

Cathryn Pender

Cathryn Pender is Grants Director of the charity.

Anna Clemenson

Anna Clemenson is Grants & Communications Manager for the charity.

Erik Mesel

Erik Mesel is Grants and Public Policy Manager for the charity and he is also a Board Member for London Funders and a Board Member for CVS Brent. He was previously a community development officer for the London Borough of Camden and a Neighbourhood facilitator for Bristol City Council.