Welcome to the November 2014 issue of the Factary Phi Newsletter.

Major Giving News

Manchester Business School to Receive £15m

Liberal Democrat Peer Lord David Alliance of Manchester has donated £15m to Manchester Business School.

His donation is to be invested in the construction of a new building, and the money will also be used to fund the cost of new research at the Alliance Manchester Business School, as it will now be called.

Lord Alliance made his name founding the textile group, Coats Viyella, and he is now non-executive Director of the Manchester-based N Brown Group, a home shopping company.

Speaking on his donation, Lord Alliance said: ‘Manchester as a city has done so much for me and this is my opportunity to make a meaningful difference to the next generation of managers and entrepreneurs’.

Fiona Devine, who is head of the business school, expressed her hope for further gifts to the school, adding that ‘We would expect things to follow on from this,’ adding that ‘There are always opportunities’.

Research institute to receive £5m

The Royal Free Charity is set to receive a massive £5m donation from the family owned Pears Foundation.

Reportedly the largest ever donation to have been made by the foundation, the money will be used to fund the construction of a new, world-class medical research institute next door to the Royal Free Hospital.

A large proportion of this new building will be dedicated to applied medical research, where leading academics will collaborate to accelerate research into the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of some of today’s major diseases.

Trevor Pears, who is Executive Chair of the foundation said: ‘My brothers and I are proud to support our local NHS hospital. Our family business is based in Hampstead and over the years we have developed a strong relationship with the Royal Free Charity and had the privilege of meeting many of the fantastic nurses, doctors and other staff who work at the hospital. The Royal Free London has a well-earned reputation as one of the UK’s leading teaching hospitals and with the exciting partnership with UCL, we are confident this new institute will deliver research breakthroughs and treatments for the benefit of thousands of patients in London and across the UK. We are honoured to have the building named after our family’.

The Royal Free Charity and UCL need to raise a total of £42m for the project, and a further £25m has also been targeted in order to support five research teams who will be based at the new facility.

Report: ‘Returns Policy? – What the Next Decade Holds for Social Investment’

This month, we have included our summary of several chapters from a recent report on the future of social investment amongst charities, conducted by Rhodri Davies on behalf of the Charities Aid Foundation.

The report is entitled ‘Returns Policy? – What the Next Decade Holds for Social Investment’, and in particular, our summary discusses some of the various investment strategies that exist, as well as some recommendations on the future of social investment.

Demands and Issues – The Financial Needs of Charities

According to the report, social investment should first and foremost be concerned with meeting the financial needs of not-for-profits, and not upon over-ambitious predictions and rhetoric over results. This means providing charities with easily accessible financial products that meet with their needs, which could in turn encourage a number of other, similar organisations to overcome their sense of scepticism and get more involved in social investment.

Policy Drivers

Government policy obviously plays a very clear role in the shaping of the work of charities and social enterprises, both in terms of what an organisation does, and what it does not do. Therefore by extension, government policies will also have an effect on the demand for social investment itself. However, it should be noted that while there may be some government policies that are specifically designed to stimulate demand, others policies may have a more subtle effect simply because they affect and change the broader policy environment.

For example, the growth of ‘Payment by Results’ in public service outsourcing has opened the door to social investment in a number of ways. The most straightforward example being that charities who take on these contracts can find themselves facing a funding gap. Therefore in order to resolve this, social investors who are interested in supporting a particular outcome can provide affordable finance in order to meet the capital requirement.

According to the report, this approach can be taken further in the form of Social Impact Bonds, an investment vehicle which allows a range of investors to pool their money and then use it to finance organisations who will then deliver on their required outcomes.

Once this is done, investors then receive a financial return dependant on the extent to which targets are met and exceeded.

Supply Issues – Charities and Charitable Foundations

Charities, it is argued, are not just part of the demand side of social investment; they could equally be important players on the supply side too. The reason for this is that many charities also have significant assets which can be invested commercially in order to get a financial return, which can then ultimately be put towards furthering their charitable aims. However, there is also the potential for at least some if this money to be put aside for social investment, and to therefore deliver in both a financial and social sense for the charity in question.

This is particularly true of endowed charitable foundations, as their traditional model is to generate income in the form of investments and then give this out in the form of grants that that are in keeping with their charitable goals. Despite this however, there is still a good deal of uncertainty amongst their trustees regarding social investment. This is partly because public guidance on this matter, published by the Charity Commission, does not have legal force, and also because many foundations also have two separate trustee committees that deal with investments and spending, while social investment can be seen as a combination of the two.

Co-mingling and co-investment

Social investment is also more complex than a single investor putting money into a single charity. Indeed, either because of the scale of the capital requirements, or in order to mitigate risk, many social investment deals involve a number of different funders pooling their resources, which can then be used to support a range of different organisations.

Of course, the complex nature of these arrangements will typically raise a number of challenges that are both practical and theoretical. Chief among them being the reality that involving a large number of different funders will typically make the deal itself more complex, and therefore introduce some additional transaction costs. In these cases, circumstances may also require the creation of a ‘special purpose vehicle’ to host and manage the investment, or the use of an existing intermediary, which will also add an additional layer of expense.

This sense of ‘co-mingling‘ between different investors in various different financial circumstances can present some real challenges for charities and social enterprises who may be on the receiving end, and of course, there may also be a number of financial risks for investors themselves.

To combat this, the report argues that investors should be presented with a more sophisticated understanding of the risks involved, and also in the context of its social and financial returns. This would then allow them to make more informed decisions about the levels of risk and the rewards of making social investments.

Corporate social investment

According to the report, corporate social investment is an area of great potential. However, it is important to distinguish between organisations who use their own money, and those who instead choose to offer tailored financial products and services (although some do both). Aside from these, there is also the potential for businesses to provide support that is not solely financial. For example, some may choose to provide in-kind help in the form of business advice or mentoring, so that charities and social enterprises may become better prepared for social investment in the future.

A mixture of the two can be a particularly potent asset for small non-profit organisations, as they will receive invaluable assistance that they would otherwise almost certainly be unable to afford.

Role of Big Society Capital (BSC)

The government-backed wholesale social investment fund has around £600m in assets, which would make the UK government a world leader in supporting social investment.

However since its launch in 2012, there have been some undeniable issues surrounding Big Society Capital. Chief among them being that because of its structure and operating principles, BSC is committed to covering its owns costs and ultimately providing a reasonable rate of return for its investors within the first couple of years. While this is not unreasonable, the rate of interest required for this means that the finance on offer may be unaffordable for a large number of charities and social enterprises.

Below, we have included some of CAF’s key principles regarding the future of social investment.

Demand

- Grant funding should be used to support charities in order to get them ‘investment ready’. Charities and their trustees should be provided with all the necessary support allowing them to develop their skills, and in order to identify and manage their own financial needs. Both new and existing sources of grant funding should be used to further this aim.

- Payment-by-Results contracts must work for charities and social enterprises. While they do have huge potential, PbR contracts must still be designed carefully if they are to work for both the voluntary sector and for social investors. These contracts should be developed to include a mixture of core funding and at-risk payments, and there must also be sufficient time in the contract process for investors to perform due diligence.

- Community assets and services are a huge opportunity. As such, charities and social enterprises should take advantage of the new rights to challenge local service delivery and to buy community assets.

Supply

Clickhere for a full version of the report.

Phi in Numbers October 2014

Organisations operating in areas related to Rights, Law & Conflict are perhaps by definition the most controversial group of charities that can be found on Phi. They are also in a minority – only 5,173 (1%) out of the total 524,796 records on Phi feature these elements amongst their Activity Types – although this may significantly under-represent the number of organisations who undertake campaigning work as a part, but perhaps not the major part, of their work.

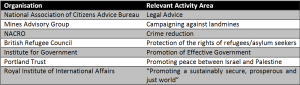

Major organisations included in this category include:

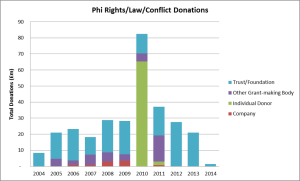

Amounts Donated

The total value of donations with a Rights/Law/Conflict connection on Phi amounts to £297m – although other contributions are somewhat dwarfed by the £65m donation from George Soros to Human Rights Watch in 2010. Note that the donations of a number of Giving List entrants (such as Hans Rausing and Gordon Roddick) with ‘rights’ related interests are not included in these figures as the amount donated to individual causes is not quantified by this source.

Donor Types

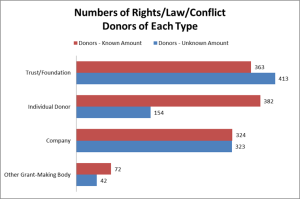

There are a total of 1,899 different donors to Rights/Law/Conflict related causes on Phi – these include 728 trusts & foundations, 536 individuals and 522 companies, with the balance being made up by other grant-making bodies such as the Big Lottery Fund, Rotary Clubs and the like.

Perhaps surprisingly, with the exception of individual donations, nearly as many records are listed with a donation amount as without (- noting of course that some donors will appear in both columns below).

Amongst trusts the average (median) grant size listed is a relatively large £42,700, amongst companies it is £15,000 and amongst individuals it is £15,800 (excluding the George Soros donation). In all cases, however, averages remain inflated by the small number of very large donations that are made.

Top Donors

The names of the top funders in this category perhaps come as little surprise, with the Sigrid Rausing Trust topping the list, followed by the Big Lottery Fund and the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation. The full de-duped list of all Rights/Law/Conflict funders with total amounts donated (as listed on Phi) is available to Phi Subscribers on request.

Methodological Notes:

- Analysis based on all donations listed on Phi against which a Rights/Law/Conflict activity type has been loaded.

- Analysis was based on the Phi database as it stood on 30th October 2014.

- Differences in naming conventions, spelling etc may result in imperfect matches between donors on some occasions.

Profile: The Derek Butler Trust

Founded in the year 2000, this trust is formed from the will of the late Derek Butler, who was a businessman and traveller who during his life had a particular interest in music and musical education. He was born in London where he spent most of his childhood, although he did also spent some time in the countryside as a evacuee during the war, and also in Northern Ireland, where he completed his national service.

By the time he finished his service in Ireland, Derek reportedly gained something of a taste for travel and from then on, he chose to spend the majority of his life abroad. Perhaps most significantly, he also spent a lengthy period in Nigeria where he was to start the business venture that made his name.

Once there, he became interested in the production of traditional clothing worn by much of its populace, more specifically, the manufacture of traditional head ties worn by Nigerian women. He joined a company specialising in this process, and after a time, he became involved in their design process and he eventually rose to become head of the company.

Despite some economic difficulties the business grew and its products, designed by him, were manufactured around the world. A great deal of its products were sold both in Nigeria, and also to Nigerian communities in the UK, as his distinctive head ties became highly sought after. The business flourished but Derek Butler later fell ill, and was diagnosed with oesophageal cancer.

After his death in 1998, The Derek Butler Trust was formed from the will of his estate, which currently makes grants in the fields of HIV, cancer, music and music education. Furthermore, the trust also makes scholarship awards for students of several universities, and in exceptional circumstances, it will also consider bursaries for individual students.

For the financial year ending 05th of April 2013, the trust reported an income of £141,164 and an expenditure of £5,940,148. Factary Phi holds 281 records of donations made to various organisations since 2005 worth a minimum of £8,839,178.

According to Phi, the average size of donations made by the trust is £32,616 and the largest proportion of these donations have been made to causes associated with Arts/Culture (107), followed by Education/Training (46), Children/Youth (24), Sports/Recreation (17), Welfare (16), Development/Housing/Employment (10), Health (6), General Charitable Purposes (6), Disability (6), Rights/Law/Conflict (5), Environment (3), Heritage (2), International Development (1), Mental Health (1), Religious Activities (1).

The Trustees

Hilary Guest

Hilary Guest is a solicitor and a consultant with Underwood Solicitors LLP. She is a Director of Avon House Preparatory School Ltd, The Sheila Ferrari Dyslexia Centre Ltd, and she is also a Trustee of The Joseph Charity and the Cecil Higgins Art Gallery.

Reverend Michael Fuller

Reverend Michael Fuller is the Rector of St John’s Shaughnessy Anglican Church in Vancouver, Canada. Prior to this, he was the Vicar of the parishes of Holland Park in Kensington, London and he was a businessman in the corporate world, and also an engineer.

James Mclean

James Mclean is a Partner with Underwood Solicitors LLP and he was previously a solicitor with the same firm. Furthermore, he is a Director of General Sewing Machines & Accessories Ltd and also Uanco Ltd.